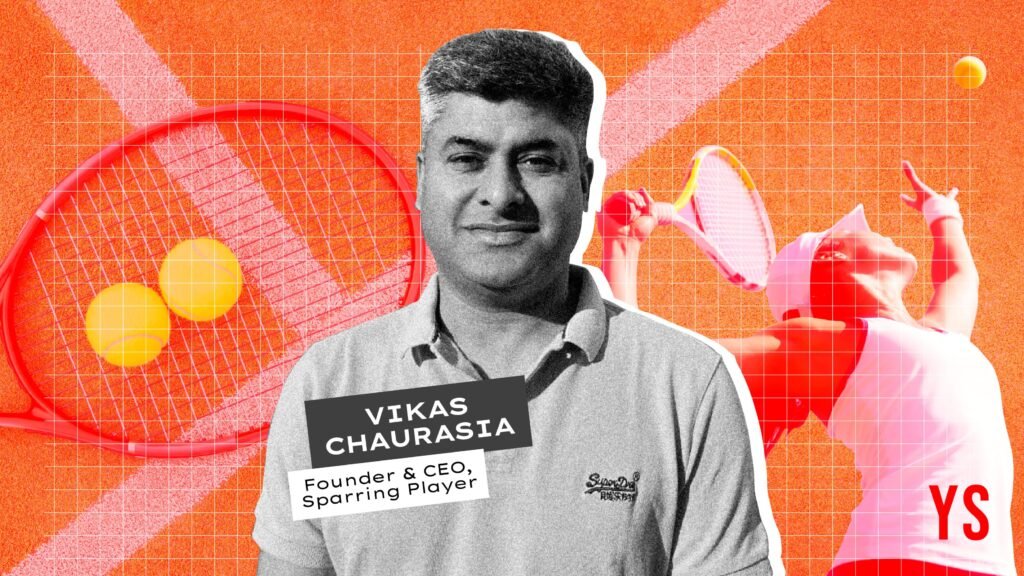

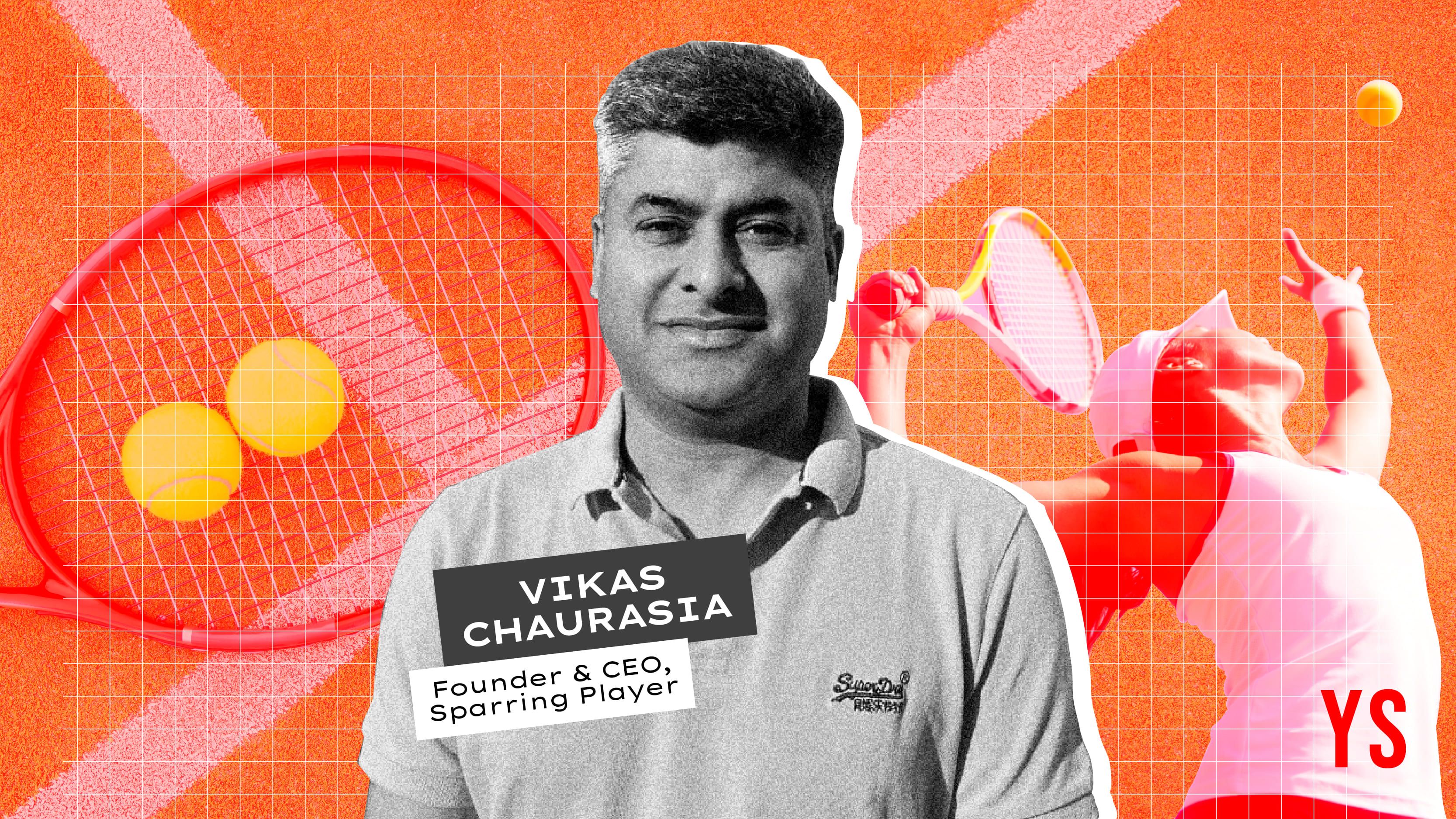

A few years ago, Yash Chaurasia—now a nationally ranked tennis player—was repeatedly faltering in tournaments despite rigorous training.

From a distance, his father Vikas Chaurasia was watching his son’s struggles—in fact, he was equally struggling as a parent who did not know what else he could do to help his child excel on the playing field.

“Yash was doing everything by the book—early mornings, endless drills, private coaching. But when match day came, it felt like starting from zero. The gap between training and performance haunted me as a father more than anything else,” says Chaurasia.

Over time, he realised that this wasn’t happening due to lack of effort, but it was because something big was missing from his son’s regimen: competitive match practice. What he needed was a ‘sparring partner’ who could keep him on his toes and help him perfect his match awareness.

Meanwhile, Chaurasia’s daughter, Taanisha, now a state-level badminton player, too faced similar challenges. As did many Indians aspiring to become professional players, especially in racquet sports.

This insight that regular practice doesn’t necessarily prepare athletes for real competition sparked the idea for Sparring Player in Chaurasia.

New Delhi-based Sparring Player is a match-play platform that connects junior athletes with experienced senior players for structured sparring sessions, designed to replicate competitive real-match conditions.

While Chaurasia had no connection with professional sports, he had an observer’s clarity—as a third person watching sports training from the sidelines.

“What I saw again and again was how our kids were being trained to hit the shuttle or the ball, but not to think or react under match stress. You can’t simulate that in a drill. You need competition. You need resistance,” says Chaurasia, who had earlier worked in the corporate world, with stints at Tata Motors and Four Points by Sheraton, where he served as the CFO.

He continues, “No matter how many hours you put in, if you’re always playing the same four people in your academy, your growth plateaus. What was missing was unpredictability, mental noise, and pace-shifting of real matches. These are things that only come when you are sparring with someone better, or different.”

This is the missing link that Sparring Player aims to fill.

How it works

Chaurasia launched the sports-tech platform in 2022 with Rs 44 lakh from his personal savings. The sports-tech startup connects junior players with top-ranked players in and around their location and facilitates paid ‘sparring sessions’ at neutral venues such as clubs, academies, and private courts. Sessions can be booked through Sparring Player’s website.

<figure class="image embed" contenteditable="false" data-id="576734" data-url="https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/6c7d986093a511ec98ee9fbd8fa414a8/WhatsAppImage2025-07-08at7-1752230921432.jpeg" data-alt="Sparring Player" data-caption="

Yash Chaurasia, Co-founder, Sparring Player

” style=”float: left; margin-right: 20px; width:50%; height:auto” align=”center”> Yash Chaurasia, Co-founder, Sparring Player

For example, an U-16 tennis player from Gurgaon preparing for an AITA (All India Tennis Association) national-level tournament in Delhi recently booked three sparring sessions with Nitin Sinha, an ATP player, ranked among the top-30 in India.

Through these sessions, which were held at a private court in South Delhi, the junior player gained valuable insights into tempo variation, shot patterns, and adapting to aggressive baseliners—nuances that are rarely taught in regular drills.

Unlike casual play, sparring involves scoring, pressure, and tactical play.

Senior players—usually those within the top 100 national ranking and with experience in the professional circuits of ATP (Association of Tennis Professionals)/WTA (Women’s Tennis Association)/BWF (Badminton World Federation), or in the national circuit—act as sparring partners.

Junior players range from school-level athletes to state and national competitors seeking match toughness.

“Match experience can’t be faked,” says Chaurasia. “You have to earn it by being on court, point after point, under pressure. And if tournaments come only once every two months, how do you stay match-ready? That’s where sparring fits in. It gives you game mileage.”

The platform currently lists over 140 verified sparring partners, including names such as B Sai Praneeth, Sourabh Verma, MR Arjun in badminton, and Vishnu Vardhan, Nitin Sinha, and Siddhant Banthia in tennis. It has facilitated 2,900 hours of sparring across 19 Indian cities, including Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Pune and supported 35 junior athletes so far.

The sparring sessions are typically priced between Rs 2,000 and Rs 3,000 per hour, depending on the senior player’s ranking and experience, the venue, and the duration and intensity of the session.

Apart from India, Sparring Player also offers sparring partners in Austria, Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, United Arab Emirates (Dubai), United States, Europe (including Spain and other European countries).

From the beginning, Chaurasia made the conscious decision not to monetise athlete connections through commissions.

“This platform was born out of a personal problem, not a business model. The moment you start taking a cut, you create doubt: Is this connection about what the athlete needs, or what the platform earns? That’s a line we didn’t want to cross.

“It’s about making sure talent doesn’t drop off the map just because there’s no one to train with, or no coach available on match day.”

Sparring Player’s revenue comes from service contracts with sporting federations.

Going global

Apart from facilitating sparring sessions in these countries, the startup has also signed service contracts with global sporting federations.

In late 2022, Chaurasia began reaching out to sports federations abroad. The first major breakthrough came from Spain—the country’s national badminton federation signed a long-term agreement with Sparring Player, whereby athletes listed on the platform support the training of senior pros from Spain, including Carolina Marin, former world number 1 and Olympic gold medallist.

“This was a moment of validation. When a country like Spain trusts a small Indian platform to support their top players, it tells you something: we have touched a real nerve in global sport,” says Chaurasia.

Since then, Italy, Sri Lanka, Morocco, Colombia, and China have come on board; listed players on the Sparring Player platform travel to these countries for sparring. A contract with Denmark, covering over 200 clubs, is in the final stages.

For these B2B service contracts, the platform charges a commission of about 9%.

These are not mere listings but service contracts, says Chaurasia—federations pay Sparring Player to deploy sparring partners, provide temporary coaches during match days, and facilitate athlete exchanges.

Sparring Player is operated by a globally distributed team. Chaurasia oversees operations and partnerships, while his son Yash, now an ATP-ranked player, manages tennis onboarding. Former India no. 1 Saurabh Sharma leads badminton onboarding in India. Yogendran Krishnan, coach of the Malaysian badminton women’s singles team, leads operations in Southeast Asia, while Sekou Bangoura, an ATP-ranked player, builds partnerships and verifies senior athletes in Europe and the United States.

Tapping into untapped potential

The International Tennis Federation estimates India’s tennis population to be 3.4 million players, roughly 10% of Asia’s player base, while the Badminton Association of India had recorded 9,851 registered players as of June 2025.

While tennis and badminton are expanding in India, opportunities are still concentrated in the metros. The smaller cities of India are largely underserved, and Sparring Player wants to address this issue.

“We get inquiries from places like Bhopal, Vizag, and Ranchi. But unless we have verified sparring partners there, we cannot offer value. That’s what we’re fixing now,” says Chaurasia.

The company is onboarding 1,000 more senior athletes, including former professionals from the district and state levels.

And it’s not just competitive juniors who are booking sessions on the platform. Adults playing tennis and badminton as a form of recreation and exercise are also booking sparring sessions.

“A lot of users are not chasing medals. They just want to feel challenged, to play against someone better. That’s equally valid. Sport is about continuous stretch,” notes Chaurasia.

.thumbnailWrapper{

width:6.62rem !important;

}

.alsoReadTitleImage{

min-width: 81px !important;

min-height: 81px !important;

}

.alsoReadMainTitleText{

font-size: 14px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

.alsoReadHeadText{

font-size: 24px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

}

Beyond match play

Sparring Player has added other services such as temporary match-side coaching, wherein parents can book experienced freelance coaches for their children during tournaments for about Rs 1,000 per match.

The platform also runs a mentorship initiative ‘Talk with Champions’ which offers video consultations with athletes such as Anand Pawar, Sai Praneeth, MR Arjun, and international coaches.

“We’re not trying to replace full-time coaches. We’re offering plug-ins—quick, timely, reliable support that fits into a player’s journey,” says Chaurasia.

The startup is helping sporting academies recruit international coaches, and has already facilitated placements for two Indian coaches in China and Europe.

Long-term vision

The long-term vision of Sparring Player is to “democratise access to match play”.

“Right now, if you are serious about your sport, you move to a metro and hope to find the right academy. We want to reverse that. With digital tools and verified networks, sparring can come to the player,” says Chaurasia.

The startup is also looking to add other sports such as table tennis, squash, and pickleball onto its platform in the next couple of years.

Sparring Player isn’t positioning itself as a court-booking app or a coach discovery service.

“We’re not just building listings,” insists Chaurasia. “We’re building rhythm—the rhythm of play, of pressure, of preparation. That’s what we felt was missing, and that’s what we’re bringing.”

Edited by Swetha Kannan