In Namakkal, a small Tamil Nadu town known more for its egg production than its restaurants, 85 food establishments did something that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago: they collectively severed ties with India’s two largest food delivery platforms.

Starting July 1, they stopped accepting food orders through online delivery platforms like Zomato and Swiggy, fed up with high commission rates and ‘hidden charges’. Years of quiet frustration had finally boiled over.

Namakkal represent the latest fracture in the symbiotic relationship between food delivery aggregators and restaurants—a relationship that, according to several restaurateurs, is turning parasitic.

The National Restaurant Association of India (NRAI) has been at odds with the two largest food aggregators for a while now. Earlier this year, the association accused Zomato and Swiggy of violating competition laws by allegedly engaging in private labelling (selling products under their own brands) through their 10-minute delivery promises. It also held discussions with Zomato parent Eternal’s CEO Deepinder Goyal over long-distance fees and has even urged its members to join the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) to counter the dominance of food delivery platforms.

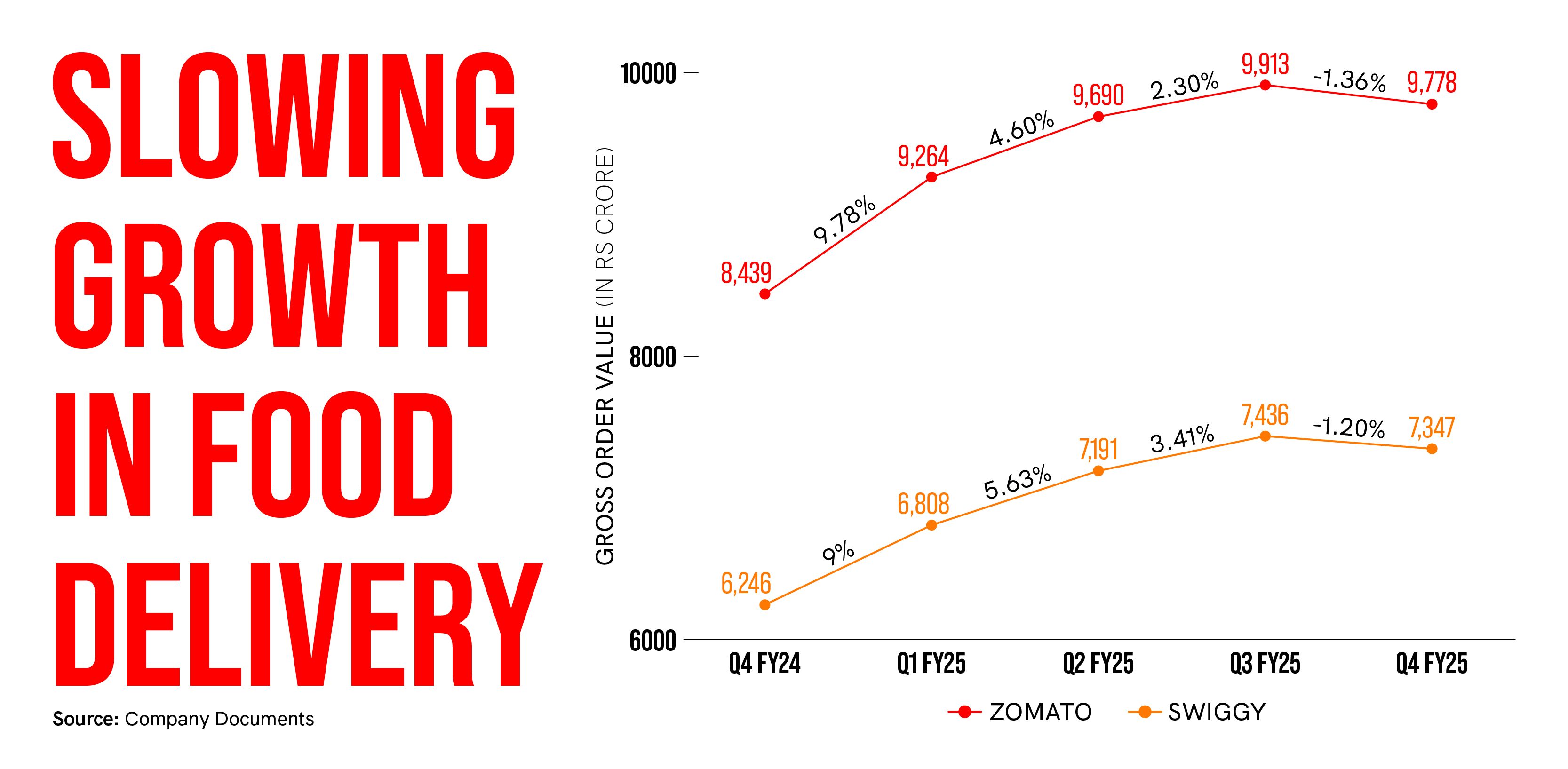

The interdependent relationship between the aggregators and restaurants has managed to hang by a thread, as the food delivery market changes. The industry is witnessing a slowdown amid lower consumer demand and rising quick commerce competition hurting operational efficiency. Both Zomato and Swiggy saw a de-growth in gross order values for the segment in Q4 FY25, declining by 1.36% and 1.2%, respectively.

Small and mid-sized restaurants are particularly nervous about the slowdown, as declining order values put them under even greater pressure. Food delivery has been a volume and average cart size game. The platform model rewards high throughput, consistency, and average order values (AOVs), making it a key negotiating power with restaurants.

The cards are stacked against middle-tier restaurants that neither operate on a scale to enable quick deliveries nor qualify for renegotiating commissions, which they complain are so high they’ve been squeezing their bottom line.

Between a rock and a hard place

The platforms had originally promised restaurants an additional revenue stream and access to consumers beyond their catchment areas. Swiggy and Zomato have largely delivered on the promise, but the dynamics have shifted as growth has slowed and investor pressure has mounted.

A general slowdown in food delivery, combined with the difficulty of scaling beyond major cities, and growing competition from quick commerce and dine-in operations, has intensified scrutiny from investors.

While Zomato’s food delivery segment more than doubled its revenue between the fourth quarters of FY23 and FY25, from Rs 380 crore to Rs 840 crore, the average monthly transacting consumers figure only grew 26% to 20.9 million. Food delivery players are essentially extracting more money from the same customer base, with retail investors pushing for additional revenue streams across advertising and partnerships.

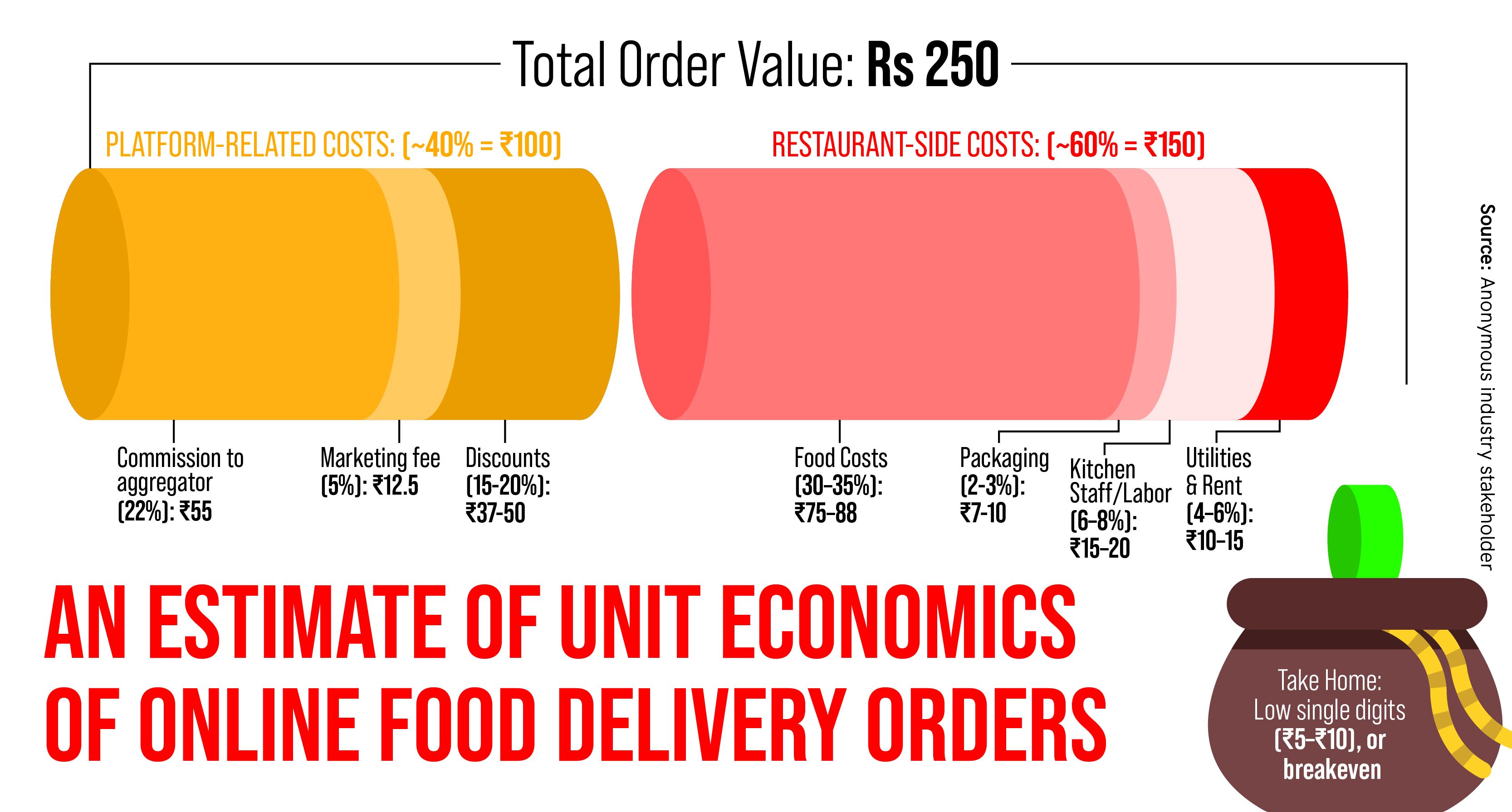

Restaurants pay fixed commissions along with platform fees and GST to food delivery aggregators. The number can range from 18% to 26%, based on the scale of the restaurant’s operations, order volume, and average cart size. Small restaurants typically pay on the higher end, while national food chains can negotiate lower rates.

“So, larger brands in each category (e.g. burger, pizza, dessert, ice cream) pay lower commissions ranging from 10%-16%, whereas the platforms charge higher commission to the smaller tail outlets, typically upwards of 20%,” explains Rishav Jain, Managing Director and Co-Lead, Consumer, Consumer tech and Retail at Alvarez & Marsal.

High commission structures and the overall cost of food delivery are the major pain points for restaurants. Some eateries YourStory spoke to revealed that commission, advertisements and discovery fees together account for 45-50% of the total payouts. At the same time, they can’t do without online food delivery as it is a key channel for most of these players.

.thumbnailWrapper{

width:6.62rem !important;

}

.alsoReadTitleImage{

min-width: 81px !important;

min-height: 81px !important;

}

.alsoReadMainTitleText{

font-size: 14px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

.alsoReadHeadText{

font-size: 24px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

}

Chasing customers

Commissions don’t explain the full story. Restaurants only pay commissions on the orders placed. To get the customers to place an order is a whole different struggle.

“Everybody is chasing visibility; they want the customer to see them. The whole gambit has been made in such a way that you have to offer discounts. So, it might not be written in a contract, but there is no way you would actually be able to get orders on the app [without discounts],” explains Gandharv Dhingra, Co-founder and CEO of Roll Baby Roll.

Mohammed Bhol, Co-founder and CEO of House of Biryan, echoes a similar sentiment. “Whether your commission is 15% or 30%, what are you going to do with that number if you don’t have customers? Without volume, commission doesn’t really hold a lot of weight,” he adds.

Restaurants routinely shell out on discovery fees to enable advertising and discounting on platforms—expenses that go beyond formal contracts—to drive volumes. From Rs 199 deals and free add-ons to keyword-based visibility and homepage placement, participation in these programmes is nudged through algorithms that reward brands offering better value and visibility.

A Chennai-based QSR (quick-service restaurant) player tells YourStory that between 2019 and 2024, advertising spends alone increased by 3X. Meanwhile, advertising elements (videos, keywords etc) on Swiggy have grown 4X over the last five years, another industry source reveals.

YourStory reached out to both Zomato and Swiggy for comments.

“When you open the app, the only thing which is publicised is the discounts… If you don’t participate, you won’t get visibility,” explains Dhingra.

“One out of every two customers doesn’t know what they want to eat. So you want to be in the top 50 listings on the app. That’s where the pressure to spend on visibility kicks in,” explains Sagar Daryani, Co-founder and CEO, Wow! Momo, and NRAI President.

While discovery attracts users who gravitate towards steal deals, restaurateurs consider it a burden and a necessary evil.

“Right now, it’s definitely a burden—and a lot of it stems from the fact that it’s a duopoly. These platforms play you along, saying things like, ‘Your competition has spent so much here, why don’t you?’ When you start seeing more traction on one app, you feel the need to push harder on the other to balance market share. The moment more players enter the space, this burden will start to ease,” adds Daryani.

Burger Singh, a QSR chain which primarily operates on a franchise model, sees almost 50% of its total orders from online channels. The company has shifted its focus to driving throughput by focusing on running localised campaigns based on competition in the region.

“Food delivery margins are definitely shrinking at a unit level, but for us, it’s a volume game. Even if the unit margin decreases, as long as the overall margin in absolute terms is growing, that’s the metric we’re chasing—for ourselves and for our partners,” says Sawan Kadyan, Head of Revenue at Burger Singh.

The unknown loyal consumer

Cloud kitchens and QSRs are now looking to build their dine-in options in a bid to lower their reliance on food aggregators.

Chennai-based Roll Baby Roll, which initially started as a cloud-based QSR for wraps and rolls, expanded to 15 outlets in the past two years. “We realised [online is] not how you build a brand or create a real identity if you want to scale. So, we moved into retail as well because customer loyalty on delivery apps is next to negligible. People are just looking for the next best discount or deal,” says Dhingra.

“Once consumers physically connect to the store, it allows me to price myself at a certain premium rather than just focusing on discounting,” he continues.

.thumbnailWrapper{

width:6.62rem !important;

}

.alsoReadTitleImage{

min-width: 81px !important;

min-height: 81px !important;

}

.alsoReadMainTitleText{

font-size: 14px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

.alsoReadHeadText{

font-size: 24px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

}

The lack of data showing repeat orders and profile visits is another woe for restaurants. Without any customer insights, restaurants are throwing a shot in the dark with discounting and discovery campaigns, unable to track customer loyalty.

“Once you know your customer data and how often the same customers come to you offline and in the online space, you don’t need to be visible to everyone. You target visibility only where it’s needed and can channelise customised offers for different sets of customers, resulting in better ROI on marketing spends,” explains Daryani.

According to the industry source quoted above, restaurants already have access to data, including order frequency and AOVs, but platforms can’t provide them with consumer details like their mobile numbers.

To increase order volume, middle-tier restaurants need to know where their customers are. After all, volume, consistently high AOVs, and advertising spends are the only leverage small- and mid-sized restaurants bring to the negotiating table.

“Your average order value really matters. If the platform takes 20% as commission, that’s a huge difference between a Rs 700 order and a Rs 250 one. The cost to deliver is the same, but the returns aren’t,” explains Bhol. “Volume matters, too. And then there’s repeat orders—do customers love you and are they coming back?” he adds.

While some restaurants looked to ONDC as a neutral, low-cost alternative to the dominant aggregators, it hasn’t yet emerged as a viable third option. Its fragmented approach with multiple buyer and seller apps has hurt accountability, with further concerns around customer experience, logistics consistency, and brand visibility.

“The issue isn’t just whether restaurants are listed on ONDC. It’s that customers aren’t there in any significant way yet,” the House of Biryan co-founder notes.

Last month, ride-hailing app Rapido launched a new food delivery service, Ownly, in select parts of Bengaluru, promising restaurants half the commission rates compared to Zomato and Swiggy. However, it remains to be seen whether it can successfully challenge the duopoly or fade to the margins like Foodpanda and Ola Cafe.

(Feature image and infographics by Nihar Apte.)

Edited by Kanishk Singh